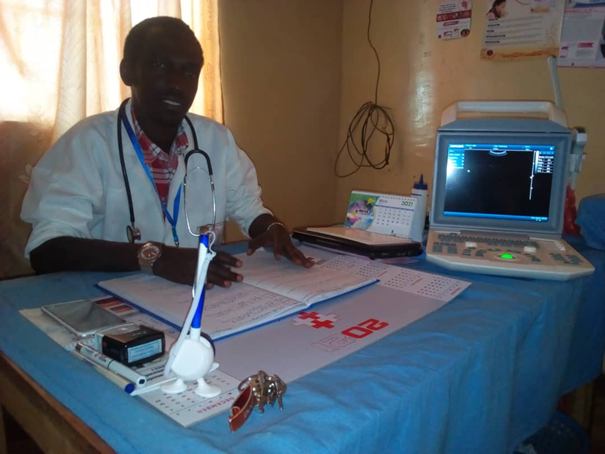

Congenital malformations in various forms are a reality in Burundi. Some of them can be predicted during ultrasounds, others are only noticed at birth. According to Dr. Thierry Nshimirimana, Head of the Centre Medical Espoir de Kayogoro, Makamba of the Association Iprosarude (Initiative for the Promotion of Rural Health and Development), the only way to detect congenital malformations is through ultrasounds. However, low participation in prenatal consultations increases the rate of births with malformations in Burundi.

Each year, more than 7.9 million children, or 6% of all births worldwide, are born with a birth defect. About 7% of all neonatal deaths worldwide are due to birth defects (WHO, 2008).

According to Dr. Thierry Nshimirimana, congenital malformations are also known as birth defects. Although their causes are often unknown, certain genetic and environmental factors, as well as infections, increase the risk of developing these defects.

“Some birth defects are noticed after birth, while others are visible through ultrasound scans during prenatal visits. Dr. Thierry continued.

Ultrasound, detection of congenital malformations

During a pregnancy, ultrasound allows to study the vitality and the development of the fetus, to detect anomalies or to determine the sex of the child.

As Dr. Thierry Nshimirimana explains, a congenital malformation of a fetus is detected during an ultrasound called morphological ultrasound. This is usually done around the 5th month of pregnancy and allows for early detection of problems that require rapid treatment. Sometimes, they are not compatible with life and in this case, a college of doctors can decide, with the consent of the couple, to terminate the pregnancy. In other cases, these malformations are compatible with life and in this case, the pregnancy is controlled until the birth of the baby, which will then undergo an appropriate morphological correction.

Unfortunately, the rate of participation in this type of consultation leaves much to be desired in Burundi. As a result, congenital malformations are noticed too late. In a report conducted by ISTEEBU in 2012, only 33% of pregnant women make the recommended number of prenatal visits, 21% make their first prenatal visit at an early stage of pregnancy, 32% at 6 to 7 months of pregnancy. This compromises the effectiveness of prenatal care.

Why the low participation rate?

Most pregnant women, especially in rural areas, only seek prenatal care when they feel unwell. But if they feel healthy, they completely forget about prenatal visits and ultrasounds.

There are some who have not yet understood the added value of ultrasounds. “Without lying, I only do an ultrasound when I don’t feel well. However, I am very interested in the ultrasound of the second trimester of pregnancy, because I can know the sex of my child. I don’t see the point of doing all the ultrasounds,” said Marie Goreth Mugisha, a resident of Gishubi commune in Gitega province.

Geographical barrier

Burundi has about forty public and religious hospitals equipped to perform ultrasounds. In urban areas, there are also private hospitals with an ultrasound service, but this is still insufficient.

However, the long distances to be covered and the poorly developed means of transport constitute a barrier to access to ultrasound for some pregnant women, especially those in the interior of the country. The poor performance of the equipment and technicians may also be a shortcoming.

Imagine a woman from the commune of Gishubi in the province of Gitega who does not have the 10,000 FBu for an ultrasound scan in a private hospital and who, in addition to her pregnancy-related weakness, is forced to get up early and not only walk more than 20 km to get to the public hospital in Gitega, but also has to wait for the entire line of patients from other communes, since this province has very few public health structures that can perform ultrasounds.

“We have to travel miles to get to the health facilities that have ultrasound services. This is not always easy given the fragile health of pregnant women,” said Ms. Léa Iconayigize, from the Buraza commune in Gitega province.

It should be noted that Burundi does not have statistics on cases of congenital malformations in the country. However, gynecologists report that they often see such cases. Iprosarude has established clinics in the provinces. This makes it easier for pregnant mothers in rural areas to access the ultrasound service. However, Iprosarude invites all stakeholders to contribute to the reduction or, failing that, the eradication of this scourge of congenital malformations.

Recent Comments